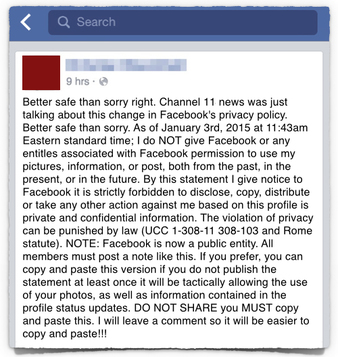

I don’t care how smart your friends are; some of them just posted a fake “Privacy Notice” that purports to protect your data from the prying eyes of Zuckerberg’s Bot Army. The notice reads something like this:

"Better safe than sorry ... Channel 11 News was just talking about this change in Facebook's privacy policy. As of September 30st at 03:50 p.m. Western standard time, I do not give Facebook or any entities associated with Facebook permission to use my pictures, information, or posts, both past and future. By this statement, I give notice to Facebook it is strictly forbidden to disclose, copy, distribute, or take any other action against me based on this profile and/or its contents. The content of this profile is private and confidential information. The violation of privacy can be punished by law (UCC § 1-308- 1 1 308-103 and the Rome Statute)."

This is pure codswallop. I’ll explain why, but its going to take a while to come to my point, so let me preview where I’m heading: the fake privacy notice is an example of people using legal sounding jargon to make something absurd sound believable. What bothers me about this fake privacy notice is that it creates an aura of credibility by exploiting the reader’s assumption that he or she will not be able to understand legal language. That assumption is inconsistent with living in a democratic society.

So why do I say this post is nonsense? First, you agreed to Facebook’s Terms and Conditions when you created your account. You agreed that Facebook might change these terms, and that as long as you kept your account open, you would be OK with these changes. You can’t decide now to change Facebook’s obligations to you by making a post telling them that you don’t like the way Facebook might handle your information. If you don’t like Facebook’s terms, you have a pretty simple way to get out of the agreement: delete your account.

Second, the “law” that the fake privacy notice cites has absolutely nothing to do with intellectual property, privacy, or social media. The Uniform Commercial Code is a set of statutes that most states have adopted that govern various types of business transactions. UCC §1-308 provides that:

(a) A party that with explicit reservation of rights performs or promises performance or assents to performance in a manner demanded or offered by the other party does not thereby prejudice the rights reserved. Such words as "without prejudice," "under protest," or the like are sufficient.

(b) Subsection (a) does not apply to an accord and satisfaction.

This statute boils down to this: if you are contesting whether you really owe someone money, but for any reason you want to pay them now and fight about it later, there is a way to pay them without admitting that you should. This statute has nothing to do with privacy or intellectual property.

The fake privacy notice goes on to cite to UCC §1 308-103. As best I can tell, there simply is no such statute.

The citation to the Rome Statute is even more bizarre. The Rome Statute is a 1998 treaty that created a permanent International Criminal Court for the prosecution of war crimes. I don’t care how much you drank last Friday, that duck face selfie you took in the bar and posted on Facebook is a crime against taste, not humanity. The International Criminal Court is not going to prosecute Facebook for using information collected from your posts.

To sum up, the legal authority that the fake privacy notice cites would be like a lawyer telling a jury not to convict a murderer because he is clean-shaven and enjoys roast beef sandwiches with smoked gouda; the premise of the argument has no connection with the conclusion.

So why does this keep getting shared? Two reasons: First, people have a kind of vague, general anxiety about privacy in a digital world, and as such they are willing to be less than skeptical when offered what looks like an easy way to protect that privacy. Second, the fake privacy notice is written with certain markers of credibility. The first of these is the reference to “Channel 11 News.” If it is on the news, it must be true. The second marker of credibility, and the one that interests me, is that the post uses legal jargon to sound credible. As I discussed, a simple Internet search of “Rome Statute,” and UCC §1-308 would be plenty to show anyone who can read at a high-school level that these laws have nothing to do with privacy, the Internet, or intellectual property. However, I suspect that many people make the assumption that they will not be able to understand the legal language, so they make no attempt to do so. By merely invoking the specter of legal jargon, the fake privacy notice tells the reader that he or she should simply believe in the power of the language contained therein for reasons the reader would not be able to decipher. Thus, the mere fact that legal sounding references are included is enough to create an illusion of credibility based on an implicit assumption that law cannot be understood.

That’s the heart of what bothers me about the fake privacy notice: it shows just how much we are willing to assume that the meaning of law is hidden by the language of law. I’m not saying that legal jargon isn’t ever needed, I’m not saying that law is always easily understood, and I am certainly not saying that you shouldn’t hire a lawyer to help you understand your legal obligations. What I am saying is that a democracy depends on the willingness of citizens to at least take a run at understanding the laws that are enacted in their name.

So the next time someone circulates a Facebook post citing legal authority, Google the citation and read the authority before you pass it on. For democracy.

"Better safe than sorry ... Channel 11 News was just talking about this change in Facebook's privacy policy. As of September 30st at 03:50 p.m. Western standard time, I do not give Facebook or any entities associated with Facebook permission to use my pictures, information, or posts, both past and future. By this statement, I give notice to Facebook it is strictly forbidden to disclose, copy, distribute, or take any other action against me based on this profile and/or its contents. The content of this profile is private and confidential information. The violation of privacy can be punished by law (UCC § 1-308- 1 1 308-103 and the Rome Statute)."

This is pure codswallop. I’ll explain why, but its going to take a while to come to my point, so let me preview where I’m heading: the fake privacy notice is an example of people using legal sounding jargon to make something absurd sound believable. What bothers me about this fake privacy notice is that it creates an aura of credibility by exploiting the reader’s assumption that he or she will not be able to understand legal language. That assumption is inconsistent with living in a democratic society.

So why do I say this post is nonsense? First, you agreed to Facebook’s Terms and Conditions when you created your account. You agreed that Facebook might change these terms, and that as long as you kept your account open, you would be OK with these changes. You can’t decide now to change Facebook’s obligations to you by making a post telling them that you don’t like the way Facebook might handle your information. If you don’t like Facebook’s terms, you have a pretty simple way to get out of the agreement: delete your account.

Second, the “law” that the fake privacy notice cites has absolutely nothing to do with intellectual property, privacy, or social media. The Uniform Commercial Code is a set of statutes that most states have adopted that govern various types of business transactions. UCC §1-308 provides that:

(a) A party that with explicit reservation of rights performs or promises performance or assents to performance in a manner demanded or offered by the other party does not thereby prejudice the rights reserved. Such words as "without prejudice," "under protest," or the like are sufficient.

(b) Subsection (a) does not apply to an accord and satisfaction.

This statute boils down to this: if you are contesting whether you really owe someone money, but for any reason you want to pay them now and fight about it later, there is a way to pay them without admitting that you should. This statute has nothing to do with privacy or intellectual property.

The fake privacy notice goes on to cite to UCC §1 308-103. As best I can tell, there simply is no such statute.

The citation to the Rome Statute is even more bizarre. The Rome Statute is a 1998 treaty that created a permanent International Criminal Court for the prosecution of war crimes. I don’t care how much you drank last Friday, that duck face selfie you took in the bar and posted on Facebook is a crime against taste, not humanity. The International Criminal Court is not going to prosecute Facebook for using information collected from your posts.

To sum up, the legal authority that the fake privacy notice cites would be like a lawyer telling a jury not to convict a murderer because he is clean-shaven and enjoys roast beef sandwiches with smoked gouda; the premise of the argument has no connection with the conclusion.

So why does this keep getting shared? Two reasons: First, people have a kind of vague, general anxiety about privacy in a digital world, and as such they are willing to be less than skeptical when offered what looks like an easy way to protect that privacy. Second, the fake privacy notice is written with certain markers of credibility. The first of these is the reference to “Channel 11 News.” If it is on the news, it must be true. The second marker of credibility, and the one that interests me, is that the post uses legal jargon to sound credible. As I discussed, a simple Internet search of “Rome Statute,” and UCC §1-308 would be plenty to show anyone who can read at a high-school level that these laws have nothing to do with privacy, the Internet, or intellectual property. However, I suspect that many people make the assumption that they will not be able to understand the legal language, so they make no attempt to do so. By merely invoking the specter of legal jargon, the fake privacy notice tells the reader that he or she should simply believe in the power of the language contained therein for reasons the reader would not be able to decipher. Thus, the mere fact that legal sounding references are included is enough to create an illusion of credibility based on an implicit assumption that law cannot be understood.

That’s the heart of what bothers me about the fake privacy notice: it shows just how much we are willing to assume that the meaning of law is hidden by the language of law. I’m not saying that legal jargon isn’t ever needed, I’m not saying that law is always easily understood, and I am certainly not saying that you shouldn’t hire a lawyer to help you understand your legal obligations. What I am saying is that a democracy depends on the willingness of citizens to at least take a run at understanding the laws that are enacted in their name.

So the next time someone circulates a Facebook post citing legal authority, Google the citation and read the authority before you pass it on. For democracy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed